“Cytoplasmic Male Sterility Declines in the Presence of Resistant Nuclear Backgrounds”

Fanny Laugier, Kévin Béthune, Florian Plumel, Céline Froissard, Jean-Marc Donnay, Timothée Chenin, François Rousset, and Patrice David: Read the article

A membership society whose goal is to advance and to diffuse knowledge of organic evolution and other broad biological principles so as to enhance the conceptual unification of the biological sciences.

Posted on

by

Fanny Laugier, Kévin Béthune, Florian Plumel, Céline Froissard, Jean-Marc Donnay, Timothée Chenin, François Rousset, and Patrice David: Read the article

An organism is a collective endeavor, in which a motley assemblage of genes collaborates to create a structure able to protect, replicate, and disperse its creators. This ability of genes to work in cooperation to produce ever more complex organisms underpins the dazzling array of biodiversity that has evolved on Earth, from bacteria to redwoods. But what happens when genes disagree? Or, in less humanizing terms, what happens when different genes within the same organism are selected for conflicting effects on the organism? How are these genomic conflicts resolved, or not resolved, over evolutionary time?

In a recent American Naturalist publication, Laugier et al. set out to characterize the evolutionary dynamics of genomic conflict. To do this, they examined one of the most striking instances of genomic conflict known from nature – the conflict between the nuclear and the mitochondrial genomes over how resources are allocated to different gametes in hermaphroditic organisms (individuals capable of producing both male and female gametes, like most flowering plants).

Anyone who’s taken Biology 101 could probably tell you that the mitochondria are (say it with me!) the powerhouse of the cell. What introductory biology curricula often leave out, however, is that mitochondria have their own genomes separate from the nuclear genome, and so they can evolve as if they have their own agenda. But why might a mitochondrion’s agenda ever be at odds with that of the nucleus? One answer lies in the difference between how nuclear and mitochondrial genomes are transmitted to the next generation. In sexual organisms, the nuclear genome is passed on through both male gametes (e.g. sperm or pollen) and female gametes (e.g. eggs or seeds). With surprisingly few exceptions, however, mitochondria are only passed on through the female gametes. If you were a mitochondrion in a hermaphroditic organism, you might conclude that any energy your host puts into making male gametes is a waste as far as you’re concerned – if it were up to you, you’d get your host to put those all resources into female gametes instead. Amazingly, mitochondria across hermaphroditic organisms have evolved ways to do just that!

In this trait, which scientists call “cytoplasmic male sterility” (CMS), the mitochondrial genome has evolved to sabotage its host’s male reproductive capacity in order to favor its own transmission. Affected hermaphrodites become effectively female. But the story doesn’t end there: the nuclear genome can fight back! By evolving “restorer” genes, the nuclear genome can counteract the effect of mitochondrial CMS genes and restore male function. The dynamics of this ensuing tug-of-war have been the subject of much theoretical analysis but have been difficult to test experimentally.

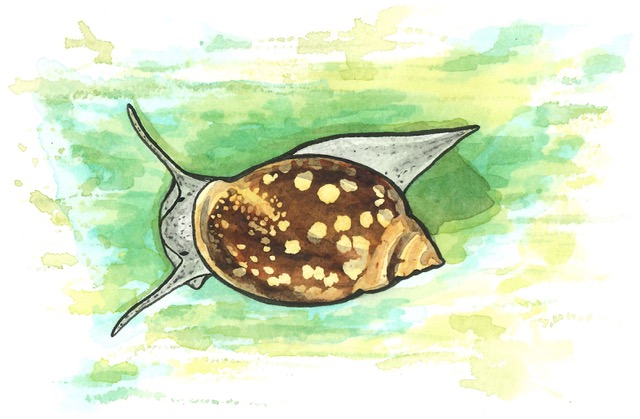

Laugier et al. approach this challenge by leveraging a recently discovered case of CMS in a hermaphroditic freshwater snail, Physa acuta. While all previously known CMS systems occur in relatively slow-growing organisms (plants), these snails have a generation time of two months, and therefore it’s feasible to grow successive generations in a laboratory setting and watch them evolve in real-time. One theory for the long-term persistence of CMS and restorer genes (neither side permanently “winning” the tug-of-war) is that the frequencies of each fluctuate up and down over time – when CMS genes are prevalent, restorer genes should rise in frequency, and when restorer genes are at high frequency, CMS genes should decline. This latter part – whether or not CMS genes decline in the presence of restorer genes – is what Laugier et al. set out to test using the Physa acuta system.

The experimenters introduced individuals carrying CMS-causing mitochondria to populations of snails that were high in frequency of nuclear restorer genes. The populations were then allowed to experimentally evolve for 11 generations. The results line up with what the prevailing theory predicts – no matter what frequency of CMS-causing mitochondria they introduced into the high-restorer population, the frequency of these mitochondria relative to wild-type mitochondria decreased rapidly over the course of the experiment.

Laugier et al. were able to determine from these results just how “unfit” the CMS mitochondrial genomes were relative to their non-CMS counterparts under these conditions. The value they calculated – a roughly 21% decline in fitness – is in line with what theoretical models predict is necessary for the long-term coexistence of CMS and restorer genes through back-and-forth fluctuations in frequency.

The authors note that while CMS represents one stark example of genomic conflict, such conflicts are ubiquitous in the natural world. Cooperation in the natural world is all around us, all the way down to the level of the gene. However, as Laugier et al. show us, these cooperative interactions may be less tranquil than meets the eye. Simmering just beneath the surface, high-stakes battles may be playing out on microscopic battlefields and over evolutionary timescales. Author Frank Herbert wrote that “each man is a little war.” Perhaps he might have gone further – if genomic conflicts as epitomized in Physa acuta are as widespread as they seem, perhaps every organism on Earth is a little war.

Andrew Cameron is a PhD student in Population Biology, Ecology, and Evolution at Emory University in the labs of Drs. Levi Morran and Nic Vega. Andrew's work aims to explore the coevolutionary dynamics of host-symbiont interactions using the model nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. When not in the lab, Andrew can often be found biking, gardening, or foraging for mushrooms.